When a patient in a clinical trial gets sick after taking a study drug, what do you do? Do you report it right away? Wait until the end of the month? Or ignore it because it was just a headache? The answer depends on one critical distinction: serious versus non-serious adverse events. Mixing these up isn’t just a paperwork mistake-it can delay life-saving safety actions or waste months of staff time on events that don’t matter.

What Makes an Adverse Event 'Serious'?

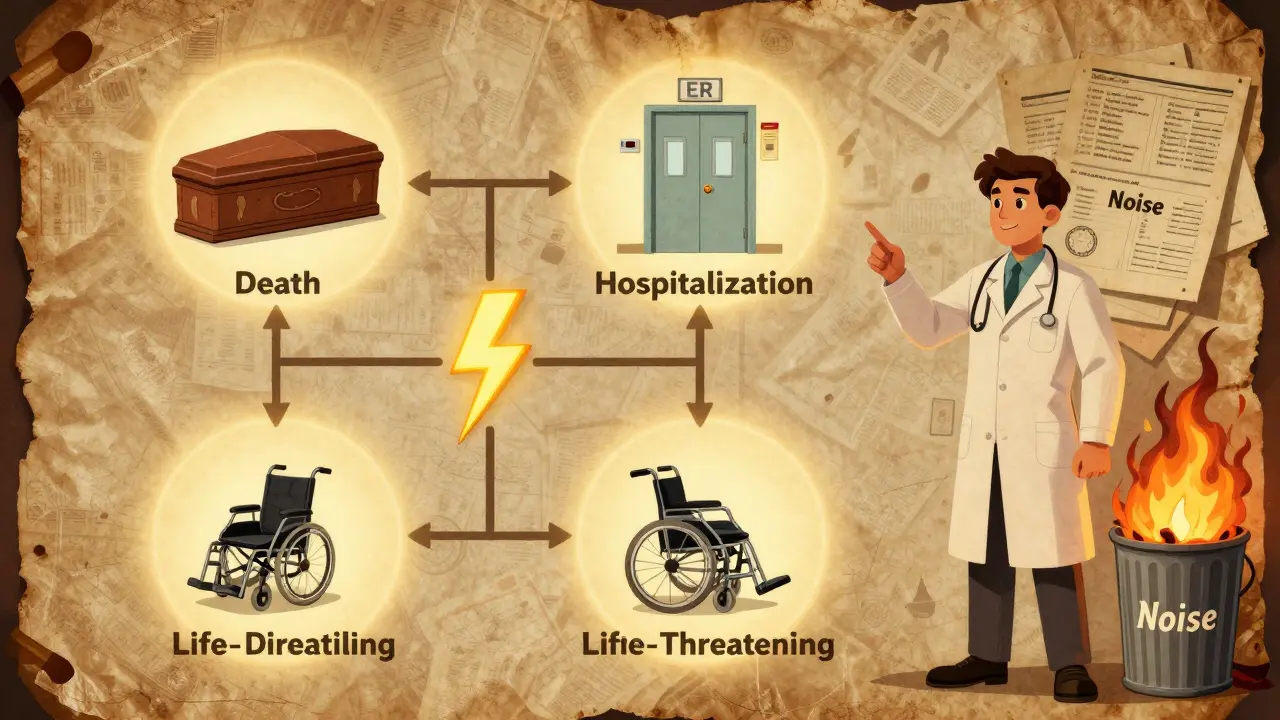

An adverse event (AE) is any unwanted medical occurrence during a clinical trial, whether or not it’s caused by the drug. But not all AEs are equal. Only those that meet specific outcome-based criteria are classified as serious adverse events (SAEs). This isn’t about how bad the symptom feels-it’s about what happened to the patient’s life or body. The FDA and ICH E2A guidelines define a serious adverse event as any untoward medical occurrence that results in:- Death

- Life-threatening illness or injury

- Need for hospitalization or prolongation of an existing hospital stay

- Persistent or significant disability or incapacity

- A congenital anomaly or birth defect

- Any event that requires medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the above

Let’s say a participant gets a bad headache after taking the study pill. If it’s intense but goes away with ibuprofen and doesn’t stop them from working or sleeping? That’s a severe symptom-but not a serious event. Now imagine that same person ends up in the ER because the headache led to a stroke. Even if the headache itself was mild, the stroke makes it serious. Outcome, not intensity, decides.

This distinction matters because it’s the line between routine documentation and emergency response. A 2022 survey of 347 research sites found that 63.4% had inconsistent seriousness ratings across studies. One site called a broken bone serious; another didn’t. Both were wrong-unless the fracture required surgery or caused permanent damage, it’s not automatically serious.

When Do You Have to Report a Serious Adverse Event?

If an event meets the seriousness criteria, the clock starts ticking-fast. Investigators must report SAEs to the sponsor within 24 hours of becoming aware of it. This rule applies regardless of whether the event seems related to the drug. A heart attack in a 78-year-old with heart disease? Report it. A fall that leads to a hip fracture? Report it. Even if the drug has nothing to do with it, you report it because the system needs to see the full picture. The sponsor then has deadlines to report to regulators:- 7 calendar days for life-threatening events

- 15 calendar days for all other serious events

These deadlines are strict. Missing one can trigger FDA inspections, fines, or even suspension of the trial. The FDA’s MedWatch Form 3500A, updated in 2022, includes checkboxes for each seriousness criterion to make sure nothing gets missed.

For Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), SAEs must be reported within 7 days. But here’s the catch: if the event is serious but expected based on the drug’s known profile, some IRBs allow a delayed report during the next routine review. That’s why protocols must clearly define which events are “expected” and which are “unexpected.”

What About Non-Serious Adverse Events?

Non-serious adverse events are everything else. Mild nausea. Temporary dizziness. A rash that fades in a week. These don’t meet the six seriousness criteria. They’re still important-but they don’t need emergency reporting. These are documented in Case Report Forms (CRFs) and reported on a schedule set by the study’s Data and Safety Monitoring Plan (DSMP). That could be monthly, quarterly, or even just at the end of the trial. Many IRBs don’t require reporting non-serious AEs at all unless they’re part of a safety signal pattern-like 10 people getting the same rare rash in a month. The key is consistency. If your protocol says you report all moderate AEs monthly, then you do it. No exceptions. But if you report every single headache, runny nose, or muscle ache as if it were life-threatening, you’re flooding the system.That’s the real problem: over-reporting. The Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative found that in 2019, 37.2% of events submitted as SAEs didn’t actually meet seriousness criteria. The European Medicines Agency reported similar numbers-nearly 3 out of 10 expedited reports were misclassified. That means teams are spending hours, days, even weeks investigating events that don’t require urgent action. And while they’re doing that, a real safety signal might be buried.

Why People Keep Getting This Wrong

The biggest mistake? Confusing severity with seriousness. “Severe” means intense. “Serious” means dangerous. A person can have a severe migraine that doesn’t require hospitalization-that’s not serious. A person can have a mild fever that leads to sepsis-that’s serious. Dr. Robert Temple, former FDA deputy director, called this confusion “one of the most persistent errors in clinical trial safety reporting.” And it’s not just new staff. Even experienced coordinators mix them up, especially in oncology or psychiatry. In cancer trials, patients often have low blood counts from chemotherapy. If a participant’s white blood cell count drops further on the study drug, is that serious? Maybe. But if it’s expected based on the drug’s profile and doesn’t lead to infection or hospitalization, it’s not serious. The same goes for “severe anxiety.” If someone has panic attacks but doesn’t need ER care or hospitalization? That’s not an SAE. A 2023 Reddit thread from clinical research coordinators had 147 comments. Eighty-nine percent said they struggled with psychiatric events. “We report ‘severe depression’ as an SAE,” one wrote. “But unless they tried to kill themselves or were hospitalized, it’s not.”How to Get It Right Every Time

There’s a simple tool to avoid mistakes: the four-question decision tree from the NIH’s 2018 guidelines. Before you report anything as serious, ask:- Did the event cause death?

- Was it life-threatening?

- Did it require hospitalization or extend an existing stay?

- Did it cause permanent disability or damage?

If the answer is “yes” to any one of these, it’s serious. If not, it’s not.

Use the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 to grade severity (mild, moderate, severe), but don’t use it to determine seriousness. They’re two separate systems. Most sponsors now use both: CTCAE for tracking symptoms, and ICH criteria for reporting.

Training helps. ICH E6(R2) requires all staff to be trained on these definitions before a trial starts. Top research institutions require annual refreshers. If your site doesn’t do this, push for it. A 2023 survey found that 98.7% of top 50 institutions do.

Technology is helping too. AI tools now correctly classify seriousness in 89.7% of cases-better than humans. But they’re not perfect. Human review is still required. The FDA’s 2024 pilot program using natural language processing to auto-triage reports is already cutting processing time by nearly half in early tests.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

This isn’t just about compliance. It’s about money, time, and patient safety. The global clinical trial safety market hit $3.27 billion in 2022. Over 40% of that-$1.3 billion-went to managing adverse event reports. Deloitte found that 62.7% of those costs came from processing non-serious events that were mislabeled as serious. Think about that. Nearly $1.2 billion a year spent chasing ghosts. And it’s not just financial. When regulators are flooded with noise, real signals get lost. Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s drug center, told Congress in 2022 that the current system is “overwhelmed by non-serious events reported as serious, diluting attention from truly critical safety signals.” The European Union’s 2022 Clinical Trials Regulation fixed this by standardizing definitions across all 27 member states. The result? A 34.8% drop in cross-border reporting errors. In the U.S., the NIH updated its guidelines in September 2023 to clarify that emergency room visits alone don’t make an event serious-unless they meet one of the six criteria. Before that, 22.1% of non-serious events were wrongly reported as serious in NIH-funded trials.What Happens If You Don’t Report?

Failing to report a serious adverse event can have real consequences:- Regulatory inspections and citations

- Fines or suspension of the trial

- Loss of funding or institutional approval

- Legal liability if harm occurs and wasn’t documented

Even worse? You might miss a pattern. If three patients in a trial develop liver failure, and you don’t report the first two because you thought they were “just bad lab results,” the third could be preventable.

On the flip side, reporting every minor symptom as serious makes your team look unprofessional. Regulators start to ignore your reports. Your IRB stops taking them seriously. You become the “boy who cried wolf.”

Bottom Line: Know the Rules. Follow the Process.

Serious adverse events are not about how bad the patient feels. They’re about what happened to their life. Death. Hospitalization. Disability. Life-threatening events. That’s it. Non-serious events? Document them. Track them. Look for patterns. But don’t treat them like emergencies. Use the four-question checklist. Train your team. Use the right tools. And never, ever confuse severity with seriousness.When in doubt, report it. Then double-check. But make sure you’re reporting the right thing-for the patient, for the science, and for the people who have to sort through the noise.

Is a severe headache a serious adverse event?

No, not unless it leads to death, hospitalization, life-threatening complications, or permanent disability. A severe headache that resolves with medication and doesn’t disrupt daily life is not a serious adverse event, even if the pain is intense.

Do I report an adverse event if it’s not related to the drug?

Yes. You must report serious adverse events regardless of whether you think they’re caused by the drug. The goal is to capture all safety signals, even those that turn out to be coincidental. Causality is determined later by the sponsor and regulators.

What if I’m not sure whether an event is serious?

When in doubt, report it as serious within 24 hours. Then review it with your team or sponsor. It’s better to over-report than under-report. But make sure you document your reasoning so it can be corrected later if needed.

Can a non-serious adverse event become serious later?

Yes. If a mild rash develops into a life-threatening skin reaction like Stevens-Johnson syndrome, it becomes a serious adverse event. You must update the report immediately with new information, even if the original event was non-serious.

Are all hospitalizations considered serious adverse events?

Only if the hospitalization was for the adverse event itself. If a patient is hospitalized for a planned surgery and has a minor infection afterward, the infection may be serious only if it meets other criteria (e.g., life-threatening). Routine hospitalizations for non-related reasons don’t count.

How often should staff be trained on AE reporting?

At minimum, annually. ICH E6(R2) requires training before a trial starts, and top research institutions require yearly refreshers. Training should include real case examples and the four-question seriousness checklist.

Do I need to report non-serious adverse events to the IRB?

Usually not. Non-serious AEs are typically reported only in summary form during routine continuing reviews, unless the protocol requires more frequent reporting or if they form a pattern suggesting a safety concern.

What’s the difference between CTCAE and ICH E2A?

CTCAE grades the severity of symptoms (mild, moderate, severe), while ICH E2A defines whether an event is serious based on patient outcomes (death, hospitalization, etc.). Use CTCAE for tracking symptoms and ICH E2A for deciding what to report as an SAE.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us