When a life-saving drug runs out, who gets it? This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now in hospitals across the U.S. In 2023, the FDA recorded 319 active drug shortages, with cancer drugs like carboplatin and cisplatin in critical supply gaps. For many patients, this means waiting - or worse, being told they won’t get the treatment they need. And behind every decision is a team of doctors, pharmacists, and ethicists trying to do the right thing under impossible conditions.

Why rationing happens - and why it’s unavoidable

Drug shortages aren’t new, but they’ve gotten worse. Between 2005 and 2011, the number of reported shortages jumped from 61 to 251. By 2023, it was over 300. The biggest culprits? Generic injectable drugs - especially those used in cancer care, ICU settings, and emergency medicine. A handful of manufacturers control most of the supply. When one plant shuts down for quality issues, or raw materials get delayed, there’s no backup. Hospitals can’t just order more. This isn’t about greed or negligence. It’s about fragile supply chains and low profit margins. Generic drugs cost pennies, so companies don’t invest in redundancy. When a shortage hits, there’s no stockpile. Clinicians are left making split-second choices: Do we give the last vial to the 72-year-old with stage IV cancer? Or the 28-year-old whose tumor is shrinking and has a real shot at survival?The ethical framework: Not guesswork, but a system

Left to their own devices, doctors might ration based on gut feeling, seniority, or who screams loudest. That’s not just unfair - it’s dangerous. The solution? Structured ethical frameworks. The most widely accepted one comes from Daniel and Sabin’s Accountability for Reasonableness model. It demands four things:- Publicity: Everyone must know how decisions are made.

- Relevance: Criteria must be based on medical evidence, not personal bias.

- Appeals: Patients and families can challenge decisions.

- Enforcement: There must be oversight to ensure rules are followed.

What criteria are actually used?

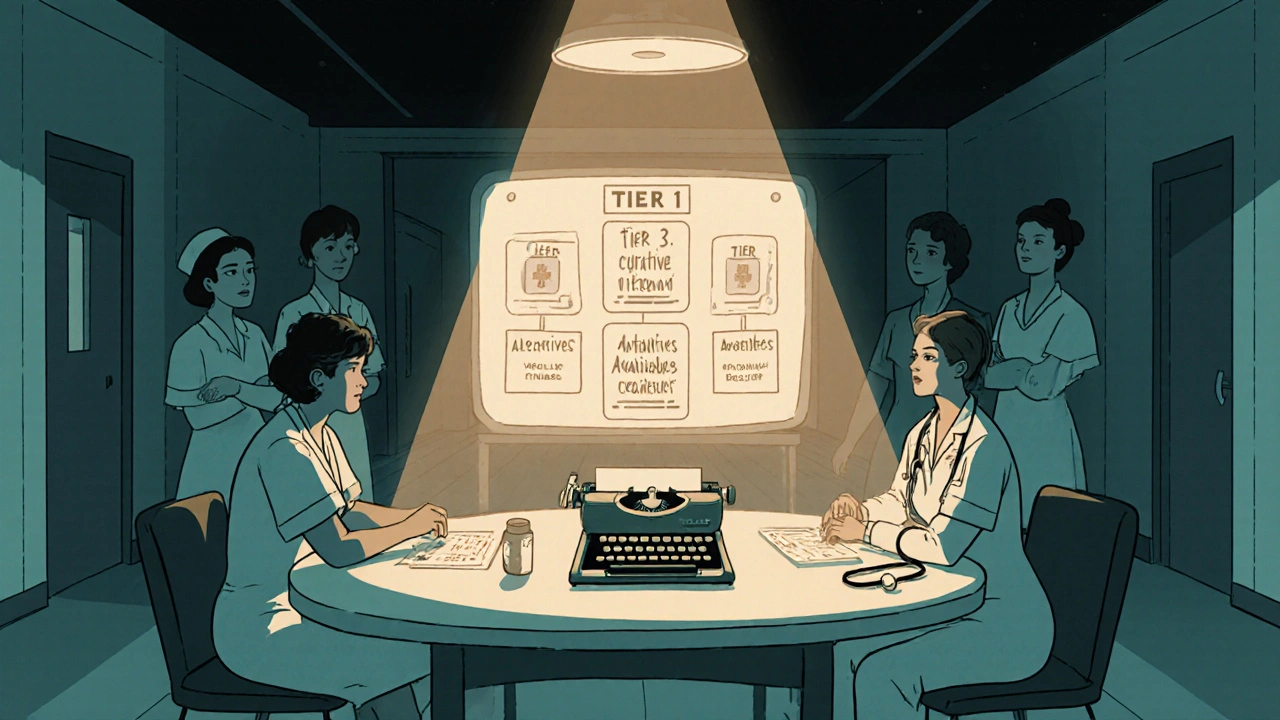

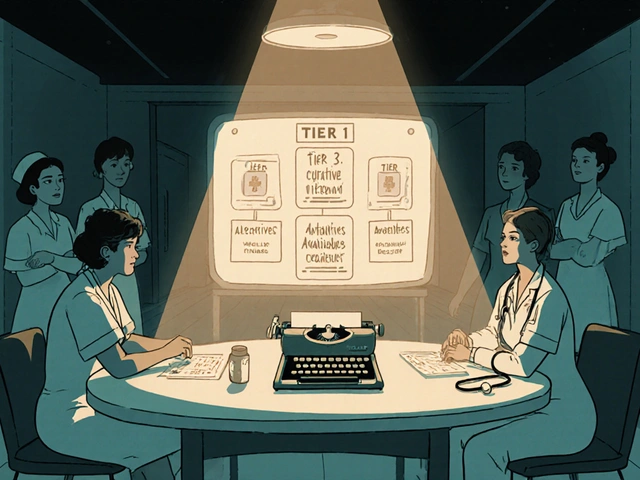

It’s not just “first come, first served.” Ethical frameworks use measurable criteria:- Urgency: Is this patient in immediate danger of death?

- Chance of benefit: Will the drug actually help? For example, carboplatin works best in patients with no prior chemo or those whose tumors haven’t developed resistance.

- Duration of benefit: Will this extend life by weeks, months, or years?

- Years of life saved: A younger patient with more life ahead may get priority.

- Instrumental value: Should a nurse or paramedic who keeps others alive get priority? Some frameworks say yes.

- Tier 1: Curative intent, no alternatives - highest priority.

- Tier 2: Palliative intent, but strong chance of symptom control.

- Tier 3: Alternative drugs available - lowest priority.

What’s working - and what’s not

Hospitals with formal ethics committees see better outcomes. A 2022 JAMA study found these hospitals had 32% fewer disparities in who got treatment. Patients from minority groups, low-income backgrounds, or rural areas were less likely to be left out. But here’s the problem: only 36% of U.S. hospitals have standing shortage committees. And of those, only 2.8% include ethicists. Most decisions still happen at the bedside. In 52% of cases, a single doctor or nurse decides who gets the drug - often without telling the patient. Clinicians are burned out. A 2022 survey found that those making ad-hoc rationing decisions had a 27% higher burnout rate. One oncologist on ASCO’s forum wrote: “I’ve had to choose between two stage IV ovarian cancer patients for limited carboplatin doses three times this month - with no institutional guidance.” Patients rarely know what’s happening. Only 36% are told their treatment is being rationed. That’s not just unethical - it breaks trust. When a patient finds out later, they feel betrayed. Some file complaints. Others never return for care.Why rural hospitals are falling behind

This isn’t a city vs. suburb issue. It’s a survival issue. Rural hospitals lack specialists. They don’t have ethicists on staff. They can’t afford to form multi-disciplinary committees. A 2022 ASHP survey found that 68% of rural hospitals have no formal rationing protocol. Meanwhile, academic centers have teams, training, and protocols. The result? A two-tier system. A patient in Chicago gets a fair shot. A patient in rural Mississippi might get nothing - not because they’re less deserving, but because the system wasn’t built for them.

What’s being done to fix it

Change is slow - but it’s coming. In May 2023, ASCO launched an online decision support tool to help clinics apply ethical criteria in real time. The FDA is building an AI-powered early warning system to predict shortages before they happen, aiming to cut duration by 30% by 2025. The National Academy of Medicine is drafting standardized allocation metrics expected in 2024. The American Society for Bioethics and Humanities is launching certification programs for hospital rationing committees in 15 states as of January 2024. Hospitals that pass will get official recognition - and access to training, templates, and legal protection. But the biggest hurdle isn’t technology. It’s culture. Many doctors still believe they should be the sole decision-makers. They fear bureaucracy. They worry about delays. But the data shows: committees save lives - and save clinicians from guilt.What patients and families can do

You can’t control the supply chain. But you can protect yourself:- Ask: “Is this drug in short supply? How are decisions made here?”

- Request a copy of your hospital’s rationing policy.

- Ask if a patient advocate or ethics consultant is available.

- Document all conversations. If you’re not told about a shortage, ask why.

The bottom line: Fairness is possible - but only with structure

Rationing medications isn’t about choosing who lives or dies. It’s about creating a system that treats everyone with dignity, even when resources are gone. It’s about replacing chaos with clarity. It’s about giving doctors a way to sleep at night without carrying the weight of impossible choices alone. The tools exist. The frameworks are proven. The problem isn’t that we don’t know how to do this right. It’s that we haven’t done it everywhere. Without standardized, transparent, and inclusive systems, drug shortages won’t just break supply chains - they’ll break trust in medicine itself.Is it legal to ration medications in the U.S.?

Yes, rationing is legal when done through transparent, ethically reviewed processes. There is no federal law requiring equal access to every drug, but hospitals must follow ethical guidelines to avoid discrimination or negligence. The FDA and professional societies like ASHP and ASCO provide frameworks that, when followed, protect institutions legally and ethically.

Who decides who gets the drug during a shortage?

Ethical guidelines recommend that decisions be made by a multidisciplinary committee - not individual doctors. This team should include pharmacists, nurses, physicians, social workers, patient advocates, and ethicists. Bedside rationing by a single clinician is discouraged because it increases bias, moral distress, and inconsistency.

Are patients told when their treatment is being rationed?

Too often, no. Only about 36% of patients are informed about rationing decisions, according to JAMA studies. This is a major ethical failure. Transparency isn’t optional - it’s required by ethical frameworks. Patients have the right to know why they’re not receiving a treatment and what alternatives exist.

Do some patients get priority because of who they are?

Ethical frameworks explicitly forbid discrimination based on age, race, income, or social status. Prioritization should be based on medical criteria: likelihood of benefit, urgency, and potential life extension. However, studies show that without strict protocols, unconscious bias still creeps in - especially in hospitals without ethics oversight. That’s why standardized systems are critical.

What can I do if I believe I was unfairly denied a drug?

Request a formal appeal through your hospital’s ethics committee. Most hospitals with ethical rationing protocols have an appeals process built in. You can also contact your state’s department of health or a patient advocacy group like the Patient Advocate Foundation. Document everything - dates, names, conversations. Unfair denial may be grounds for a complaint or even legal action if discrimination is proven.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us