Sirolimus Wound Healing Calculator

Patient Risk Assessment

Recommended Sirolimus Start Time

Low RiskStart Date: Day 7 post-op

Risk Level: Minimal risk of complications

When a patient gets a kidney transplant, the goal isn’t just to keep the new organ alive-it’s to help them live a full, active life again. But one drug that helps prevent rejection, sirolimus, can make healing after surgery much harder. It’s not a simple yes-or-no question. You can’t just avoid sirolimus altogether, because it has real benefits: no kidney damage, lower cancer risk, and fewer viral infections. But if you give it too soon after surgery, wounds may not close right. The key isn’t to stop using it-it’s to know when to start it.

How Sirolimus Slows Down Healing

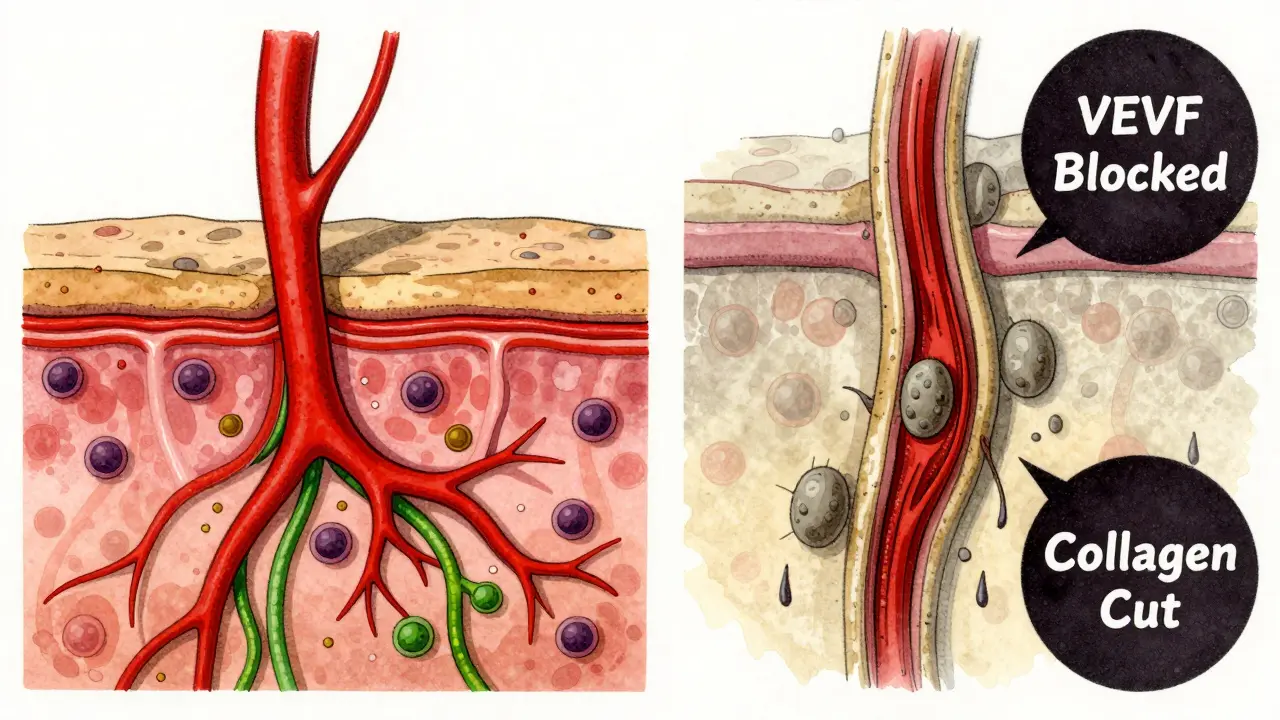

Sirolimus works by blocking a protein called mTOR. That sounds technical, but what it really means is it slows down cell growth. For a transplant patient, that’s good-it stops the immune system from attacking the new kidney. But for a surgical wound, that’s a problem. Healing needs cells to multiply fast: skin cells to close the cut, fibroblasts to build collagen, blood vessels to bring oxygen and nutrients. Sirolimus hits all of them.

Studies in rats show that when sirolimus is given at therapeutic doses, wound strength drops by up to 40%. Collagen, the main structural protein in skin, is cut back significantly. Even more telling: the concentration of sirolimus in wound fluid is two to five times higher than in the blood. That means the drug isn’t just circulating-it’s pooling right where the body is trying to repair itself.

The mechanism is clear. Sirolimus shuts down VEGF, the signal that tells blood vessels to grow. No new blood vessels means less oxygen, fewer immune cells, and slower cleanup of dead tissue. It also stops fibroblasts from multiplying and smooth muscle cells from repairing tissue. In short, the whole healing process gets stuck in slow motion.

The Real Risk: When It Matters Most

Not every surgery carries the same risk. A small skin biopsy? Probably fine. A major abdominal transplant? That’s where problems show up.

A 2008 Mayo Clinic study looked at 26 transplant patients on sirolimus who had dermatologic surgeries. The infection rate was 19.2% compared to 5.4% in those not on sirolimus. Wound dehiscence-where the incision reopens-happened in 7.7% of the sirolimus group. No statistically significant difference? That’s because the sample was small. But the numbers still raise red flags. In bigger surgeries, like liver or kidney transplants, the risk isn’t just theoretical. Lymphocele (fluid buildup), delayed closure, and infection are documented complications.

Here’s the catch: many of these complications aren’t caused by sirolimus alone. They’re caused by sirolimus + other drugs + patient factors. Steroids, antithymocyte globulin, and mycophenolate all affect healing too. And then there’s the patient’s health: diabetes, smoking, obesity, malnutrition. These aren’t minor details-they’re game-changers.

One study found that for every point higher a patient’s BMI, their odds of wound problems jumped. Obesity isn’t just a number-it’s thicker tissue, poorer blood flow, and more tension on the incision. A smoker’s wound heals 30% slower than a non-smoker’s. A diabetic with poor sugar control? Their collagen doesn’t form properly. Sirolimus doesn’t create these problems-it makes them worse.

When to Start Sirolimus: The Evolving Rule

For years, the rule was simple: don’t give sirolimus for at least two weeks after surgery. Many centers still follow that. But the latest evidence says that’s outdated.

Back in 2009, experts recommended avoiding sirolimus during the first week post-transplant. That advice came from solid animal data and early human cases. But since then, we’ve learned more. We know now that trough levels-the amount of drug in the blood-matter more than timing alone. If you keep sirolimus levels below 4-6 ng/mL during the first 30 days, you can reduce wound complications without losing immunosuppression.

Some centers now start sirolimus as early as day 7, especially if the patient is low-risk: no diabetes, no obesity, non-smoker, good nutrition. Others wait until day 14, especially after major abdominal surgery. The shift isn’t about being bold-it’s about being precise.

It’s not a one-size-fits-all anymore. A 55-year-old man with a BMI of 22, who quit smoking six weeks ago and eats well, can handle sirolimus earlier than a 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes, a BMI of 35, and protein deficiency. The drug isn’t the villain. The combination of risk factors is.

What You Can Do to Reduce Risk

If you’re managing a patient on sirolimus, here’s what actually works:

- Stop smoking at least 4 weeks before surgery. This isn’t optional. Smoking cuts oxygen delivery and cripples collagen production.

- Control blood sugar. Aim for HbA1c below 7%. Even moderate hyperglycemia delays healing.

- Optimize nutrition. Protein intake should be at least 1.2-1.5 grams per kilogram of body weight. Albumin levels below 3.5 g/dL mean higher complication risk.

- Check BMI. If it’s over 30, consider delaying sirolimus until the wound is stable. Weight loss pre-surgery helps, even modestly.

- Monitor trough levels. Keep sirolimus between 4-6 ng/mL for the first month. Levels above 8 ng/mL sharply increase complication risk.

- Consider alternatives. If the patient has multiple risk factors, tacrolimus might be safer early on. You can switch to sirolimus later, once healing is confirmed.

These aren’t just suggestions-they’re proven interventions. A 2022 study showed that when centers implemented these steps, wound complication rates dropped by nearly half, even in patients on sirolimus.

Why Sirolimus Still Has a Place

It’s easy to see sirolimus as dangerous. But let’s look at what happens without it.

Calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus and cyclosporine are the standard. But they damage kidneys over time. For a transplant patient, that means a higher chance of needing dialysis again in 5-10 years. Sirolimus doesn’t do that. It also cuts the risk of skin cancer-something transplant patients face at 65 times the normal rate.

So you’re not choosing between safe and risky. You’re choosing between two kinds of risk: short-term wound problems versus long-term organ damage and cancer.

That’s why sirolimus is still used in 15-20% of kidney transplant patients. It’s not a last resort. It’s a strategic tool. Used right, it gives patients more years of healthy life. Used carelessly, it causes avoidable complications.

The Bottom Line

Sirolimus doesn’t have to be avoided after surgery. But it can’t be rushed. The old idea-that it’s too dangerous to use early-is fading. What’s replacing it is a smarter approach: assess the patient, optimize their health, control the dose, and time it right.

Don’t look at sirolimus as a drug that breaks healing. Look at it as a drug that demands better planning. The best outcomes happen when clinicians don’t just follow a timeline-they tailor the plan to the person.

Healing isn’t just about the wound. It’s about the whole patient. And when you treat the whole patient-not just the drug or the surgery-you get better results.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us