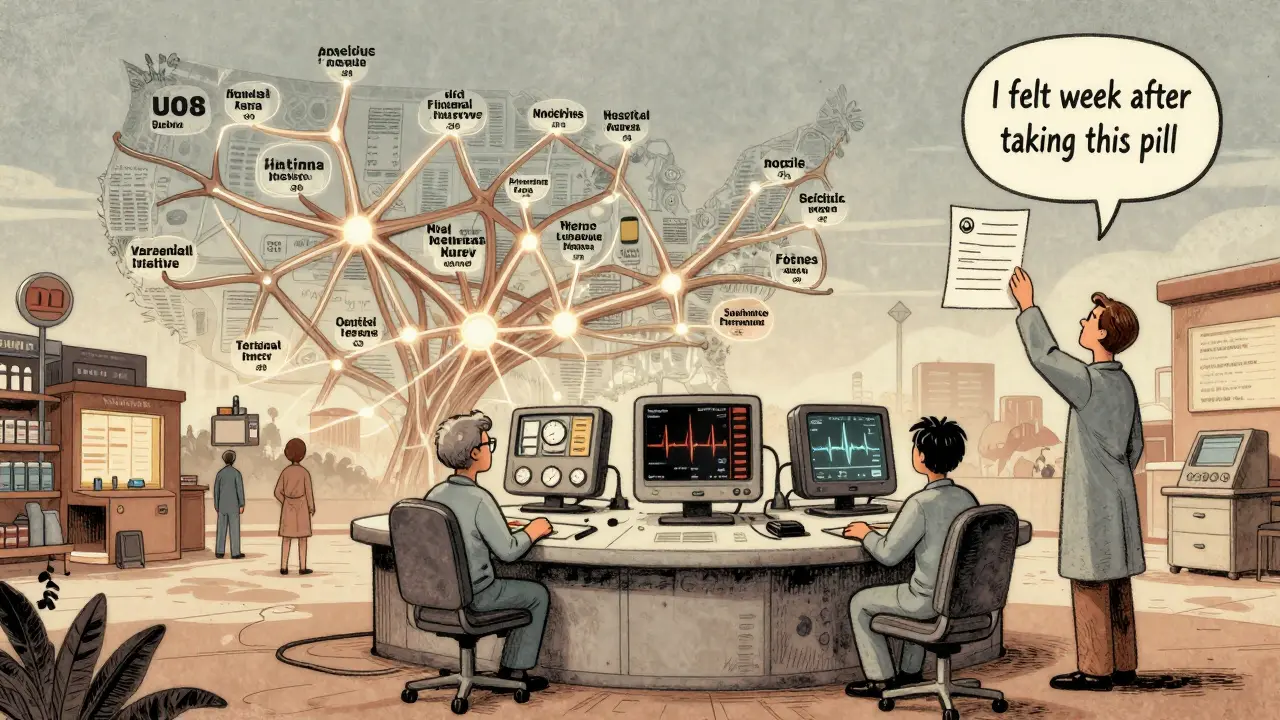

When a new drug hits the market, the work isn’t over. In fact, that’s when the real safety monitoring begins. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t just approve drugs and walk away. It keeps watching - closely, continuously, and with powerful tools - to catch problems that clinical trials missed. Clinical trials involve thousands of people, but real life involves millions. Different ages, other medications, long-term use, rare genetic reactions - these are things you can’t fully see before approval. That’s why the FDA’s postmarket safety system is one of the most complex and critical public health operations in the country.

The Backbone: FAERS and Spontaneous Reporting

At the heart of this system is the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Since 1969, this database has collected over 30 million reports of possible side effects, medication errors, and product quality issues. These reports come from doctors, pharmacists, patients, and drug manufacturers. When someone experiences an unexpected reaction - like sudden liver damage after taking a common painkiller - they or their provider can file a report through MedWatch, the FDA’s online portal. Manufacturers are legally required to report serious adverse events within 15 days. Patients and providers aren’t required to report, but they’re encouraged. The problem? Only about 1% to 10% of actual adverse events ever get reported. Many go unnoticed. Others are dismissed as coincidence. A 2023 study in JAMA Network Open found that FAERS likely misses most cases. Still, it’s the first line of defense. Analysts comb through these reports using statistical tools like Empirical Bayes Screening and Proportional Reporting Ratios to spot unusual patterns. If a certain drug suddenly shows up in 10 times more reports of a rare heart rhythm issue than expected, that’s a signal - and the FDA takes notice.Active Surveillance: The Sentinel Initiative

FAERS is passive. It waits for reports. But in 2008, the FDA launched something bigger: the Sentinel Initiative. This isn’t just a database - it’s a live network. Sentinel connects to electronic health records, insurance claims, and pharmacy databases from over 300 million people across the U.S. It’s like having a real-time pulse on how drugs behave in the wild. Instead of waiting for someone to report a problem, Sentinel proactively looks for them. For example, if a new diabetes drug is linked to a spike in kidney failure cases in the claims data from Kaiser Permanente, or if patients on a blood thinner start showing up more often in ER visits at Cleveland Clinic, Sentinel flags it within weeks - not years. By 2023, Sentinel was monitoring 190 million covered lives, far outpacing Europe’s similar system. And in late 2023, the FDA rolled out InfoViP 3.0, a machine learning tool that cut signal detection time from 14 months down to just over 6 months. That’s a game-changer.High-Risk Drugs and REMS Programs

Not all drugs are treated the same. Some carry higher risks - think cancer drugs, immunosuppressants, or medications with narrow safety margins. For these, the FDA requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). As of January 2024, 78 drugs had active REMS programs. These aren’t just warnings on the label. They can include mandatory patient education, restricted distribution, special training for prescribers, or even mandatory blood tests before each dose. For example, a drug used to treat multiple sclerosis might require doctors to complete an online certification before prescribing it. Another might only be dispensed through certified pharmacies. These programs protect patients but add layers of complexity. Pharmacies and clinics spend 80-100 hours per month just managing compliance for REMS drugs. That’s why the FDA tracks these programs closely - and why they’re one of the most effective tools for managing high-risk medications.

Who Reports, and Why It Matters

You might assume doctors are the main source of safety reports. But data shows otherwise. In a 2023 analysis of FAERS submissions, healthcare providers filed 63% of reports. Drug companies filed 31%. Patients? Just 6%. That’s a huge gap. Many patients don’t know how to report. Others think it’s pointless. A Reddit thread from June 2023 featured a cancer doctor who admitted she’d filed only three reports in five years because the process felt disconnected from her daily work. The FDA has tried to fix this. MedWatch is now online and takes about 17 minutes to complete. But awareness is still low. A 2022 FDA survey found 41% of healthcare professionals didn’t even know about MedSun, a program that recruits 350 providers specifically to report medical device problems. Patient advocacy groups like NORD report that 72% of rare disease patients feel uninformed about reporting. Without patient input, the system is blind to many real-world experiences.Challenges and Gaps

The system works - but it’s not perfect. One big problem: drugs with low usage. If only 50,000 people take a medication, it can take nearly five years for a safety signal to emerge. That’s because the statistical noise drowns out the signal. A 2021 study in Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety showed that rare drugs take almost twice as long to flag as popular ones. Another issue: delayed studies. The FDA can require drugmakers to conduct postapproval safety studies. But a 2021 Government Accountability Office report found that for 37% of drugs approved between 2013 and 2017 with known safety concerns, those studies were never started - or were delayed by over three years. Even when required, only 58% were completed on time, according to a 2021 JAMA Internal Medicine study. And then there’s the data gap. Sentinel relies on electronic records - but not all providers use them. Rural clinics, small practices, and uninsured patients often fall through the cracks. The FDA is working on this. By 2025, it plans to integrate data from the NIH’s All of Us program, which includes 1 million diverse participants. That could help catch disparities in how drugs affect different races, genders, and socioeconomic groups.

The Future: AI, Blockchain, and Bigger Data

The future of drug safety is faster, smarter, and more connected. Sentinel 2.0, launched in February 2024, adds genomic data from 10 million people. That means the FDA can now ask: Does this side effect only happen in people with a certain gene variant? That’s precision pharmacovigilance. A blockchain-based reporting pilot is scheduled for Q2 2025. The idea? Create an unchangeable, transparent record of adverse events that patients, doctors, and regulators can trust. No more lost forms. No more delays. By 2030, experts predict 75% of safety signals will come from active surveillance - not passive reports. That’s up from just 35% today. But it won’t happen without funding. The FDA’s Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology is currently operating at 82% staffing. And with gene therapies and complex biologics exploding onto the market - 40% more each year - the system is under pressure.What You Can Do

If you’re taking a new medication, pay attention. Write down any unusual symptoms - even if they seem minor. If something feels off, talk to your doctor. And if you’re not sure whether it’s related to your drug, report it anyway. You don’t need to be an expert. The FDA’s MedWatch portal is free, easy to use, and designed for anyone. Your report could be the one that prevents someone else from being harmed. The system isn’t flawless. But it’s the best we have. And it only works if people use it.How does the FDA know if a drug is unsafe after it’s approved?

The FDA uses a combination of passive reporting through FAERS (over 30 million reports) and active surveillance via the Sentinel Initiative, which analyzes health data from 300 million patients. They look for unusual patterns - like a sudden spike in liver damage cases linked to a specific drug - using statistical tools and machine learning. If a safety signal is confirmed, they investigate further and may require label changes, restrict use, or even pull the drug from the market.

Can patients report adverse drug reactions?

Yes. Patients can report side effects directly through the FDA’s MedWatch portal. While healthcare providers and manufacturers submit most reports, patient reports are critical because they capture real-world experiences that doctors might miss - like long-term fatigue, mood changes, or rare reactions. Every report helps build a clearer picture of a drug’s safety.

What is a REMS program?

A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) is a safety plan the FDA requires for certain high-risk drugs. It can include mandatory patient education, restricted distribution, prescriber training, or regular lab tests. As of 2024, 78 drugs have active REMS programs, including some cancer treatments and immune-suppressing drugs. These programs aim to reduce serious side effects while still allowing patients access to needed medications.

Why do some drug safety problems take years to be found?

Clinical trials involve thousands of people over months or a few years. Real-world use involves millions over decades. Rare side effects - like a 1-in-50,000 risk of a heart rhythm problem - simply don’t show up in small trials. Also, drugs with low usage (under 100,000 patients) can take nearly five years for a signal to emerge. Underreporting and data gaps slow detection further.

Is the FDA’s system better than other countries’?

The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative is the most advanced active surveillance system in the world, monitoring 190 million lives compared to Europe’s 100 million. The U.S. also has stricter reporting deadlines: manufacturers must report serious adverse events within 15 days, while Europe allows 90 days for expected reactions. However, the FDA still struggles with underreporting and staffing shortages, and other countries are catching up with better digital infrastructure.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us