Every year, millions of unused prescription drugs sit in medicine cabinets across the U.S.-old painkillers, leftover antibiotics, expired antidepressants. Many people don’t know what to do with them, so they keep them. Or worse, they flush them down the toilet or toss them in the trash. Both are dangerous. Flushing contaminates water supplies. Throwing them out invites kids, teens, or even pets to find and misuse them. That’s where National Prescription Drug Take-Back Days come in.

What Exactly Is a Take-Back Day?

National Prescription Drug Take-Back Days are biannual events run by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). They happen twice a year: once in April and once in October. The next one is on October 25, 2025, from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. local time. During those four hours, hundreds of law enforcement agencies across the country open their doors-or set up booths at pharmacies, hospitals, or community centers-to collect unwanted prescription medications. No questions asked. No ID needed. Just drop them off and walk away.The goal? Keep dangerous drugs out of the wrong hands and off the streets. In April 2025 alone, Americans turned in over 620,000 pounds of unused pills, patches, and capsules. That’s more than 310 tons. Since the program started in 2010, it’s collected nearly 10 million pounds total. That’s not just cleanup-it’s prevention.

What Can You Bring?

Not everything goes in the bin. The DEA is clear about what’s accepted and what isn’t.- Accepted: Pills, capsules, patches (like fentanyl or nicotine), liquids in sealed containers (like cough syrup), and ointments.

- Not Accepted: Syringes, needles, sharps, inhalers, aerosols, illegal drugs (like heroin or cocaine), or over-the-counter meds like ibuprofen or allergy pills.

Liquids must stay in their original bottles with the lid tightly closed. If it’s in a plastic bag or open container, they won’t take it. Patches? Remove them from the backing and fold them in half so the sticky side sticks to itself. That prevents accidental exposure.

Why these rules? Some items can leak, explode, or contaminate other drugs during transport. Sharps are a safety hazard for workers. Illegal drugs fall outside the DEA’s disposal mandate-they’re handled separately under criminal procedures.

Where Do You Go?

There are over 4,500 collection sites nationwide. You can find yours by visiting takebackday.dea.gov or using the Dispose My Meds app. Sites include:- Local police stations

- Fire departments

- Hospital pharmacies (like University Hospitals in Ohio)

- Retail pharmacies (CVS and Walgreens often host them)

- Community centers and public libraries

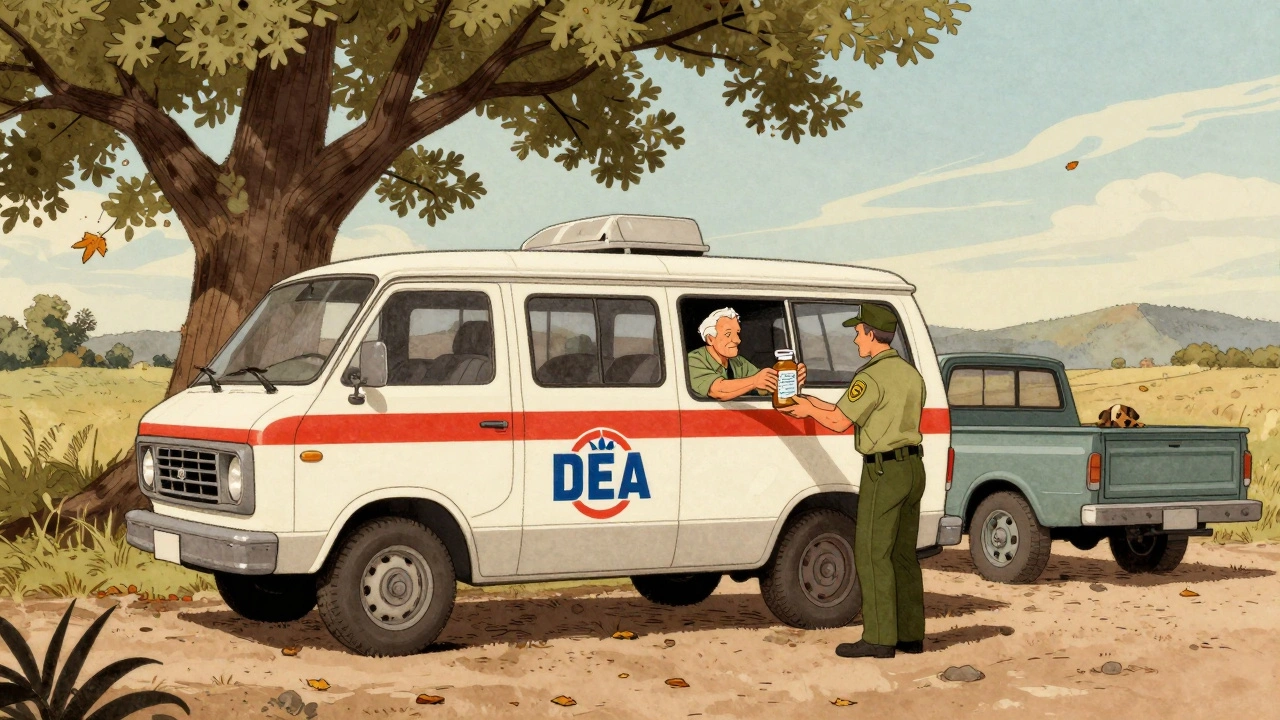

In cities, you’re rarely more than a few miles from a site. But in rural areas, it’s trickier. Some counties have only one collection point for every 50,000 people. That’s why the DEA launched mobile units in 2025-120 vans traveling to towns more than 25 miles from a fixed site. If you live in a remote area, check the website early. These mobile stops are scheduled weeks in advance.

What Happens After You Drop Them Off?

Once you hand over your meds, they’re locked in secure bins. Law enforcement officers keep custody until the end of the day. Then, all collected drugs are shipped to certified incineration facilities. They’re burned at temperatures over 1,800°F-high enough to completely destroy the active ingredients. No recycling. No landfill. No chance of recovery.This isn’t just about cleaning up junk medicine. It’s about stopping the cycle of misuse. Studies show that 57.9% of people who misuse prescription painkillers get them from family or friends’ medicine cabinets. When those pills disappear, fewer teens are tempted to experiment. Fewer parents worry about accidental poisoning. Fewer addicts have easy access to opioids.

Why Not Just Flush or Trash Them?

It’s tempting. It’s easy. But it’s harmful.Flushing sends drugs into water systems. Even wastewater treatment plants can’t fully remove pharmaceuticals. Traces of antidepressants, birth control, and antibiotics have been found in rivers, lakes, and even drinking water. That’s not just an environmental issue-it affects fish, frogs, and eventually humans.

Throwing pills in the trash? That’s a recipe for disaster. Trash collectors, scavengers, and kids can dig through bins. In 2024, the FDA estimated that 75% of Americans still dispose of meds improperly. That’s 190 million people. Take-Back Days fix that gap.

What If You Miss the Day?

You don’t have to wait six months. There are over 14,250 permanent drug disposal kiosks across the U.S.-mostly in pharmacies and police stations. CVS and Walgreens now have them in more than 1,200 locations. These kiosks accept the same items as Take-Back Days: pills, patches, liquids in sealed containers. No appointment needed. No hours to worry about.They’re not as visible as the biannual events, but they’re always open. If you’re unsure where to find one, search “permanent drug disposal near me” or check the DEA’s online locator. Some states, like South Carolina and Ohio, have partnered with hospitals to install kiosks in outpatient clinics. Ask your pharmacist-they know where the closest one is.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

In 2024, over 54,700 Americans died from opioid overdoses. That’s not just about street drugs. A huge chunk starts with a prescription. One study found that 8 million people aged 12 and older misused pain relievers in the past year. Most got them from home.Take-Back Days aren’t just about disposal. They’re about education. At many sites, volunteers hand out brochures on safe storage, signs of addiction, and how to talk to teens about meds. Some hospitals even offer free lockboxes to keep prescriptions out of reach. That’s why participation is up 37% at sites that combine collection with education.

This program works because it’s simple. No cost. No judgment. No paperwork. Just a 2-minute stop at your local police station and a small act of responsibility. And it’s backed by real results: a 27% drop in opioid overdose deaths since 2020, according to the Partnership to End Addiction.

What to Do Before the Event

Don’t wait until the day before. Here’s how to prepare:- Go through every medicine cabinet, bathroom drawer, and nightstand.

- Take out anything expired, unused, or no longer needed.

- Remove pills from blister packs and put them in a sealed plastic bag.

- Keep liquids in original bottles with caps on.

- For patches: fold them sticky-side together.

- Leave out OTC meds, vitamins, or sharps.

- Check the DEA website for your nearest site and confirm hours.

Pro tip: Do this once a year, right after the holidays or your annual check-up. It’s easier to clean out when you’re already thinking about health.

What If You’re Still Unsure?

If you’re not sure whether something can be dropped off, call your local police station or pharmacy ahead of time. Most have a dedicated line for disposal questions. Don’t guess. It’s better to ask than to risk contaminating the bin or getting turned away.And if you’re worried about privacy? Don’t be. Law enforcement doesn’t track who drops off what. No names. No IDs. No records. You’re not being investigated-you’re helping your community.

Final Thought

This isn’t just about getting rid of old pills. It’s about protecting your family, your neighbors, and your environment. Every bottle you turn in is one less chance for someone to get hurt. You don’t need to be an expert. You don’t need to make a big gesture. Just take five minutes twice a year. It’s one of the easiest, most powerful things you can do for public safety.Can I drop off my old insulin pens or syringes at a Take-Back Day?

No. Syringes, needles, and other sharps are not accepted at Take-Back Days because they pose a safety risk to workers. Instead, use a FDA-approved sharps container and bring it to your local pharmacy, hospital, or household hazardous waste facility. Many pharmacies offer free sharps disposal programs.

Are there any fees to participate?

No. National Prescription Drug Take-Back Days are completely free. You don’t pay anything to drop off your medications. No membership, no registration, no hidden charges. The program is funded by federal grants and run by law enforcement partners.

What if I live in a rural area with no collection site nearby?

The DEA launched mobile collection units in 2025 to reach communities more than 25 miles from a fixed site. Check takebackday.dea.gov for scheduled stops near you. If none are listed, contact your county health department-they may have partnerships with local nonprofits or mobile clinics that offer year-round disposal.

Can I drop off someone else’s medications, like my parent’s?

Yes. You can bring medications belonging to family members, friends, or even pets (if they’re human prescription drugs). No proof of ownership is required. The DEA’s policy is anonymous and non-judgmental-your goal is safety, not paperwork.

Why don’t they accept over-the-counter drugs?

Take-Back Days focus on prescription drugs because they’re the main source of misuse and overdose. OTC meds like aspirin or cold pills are generally less dangerous and can be disposed of in household trash-mixed with coffee grounds or cat litter to make them unappealing. Some communities have separate OTC disposal events, but they’re not part of the DEA’s national program.

Is it safe to store unused meds at home until the next event?

It’s safer than flushing or trashing them, but not ideal. Keep them locked in a cabinet, out of reach of children and teens. Consider using a lockbox. The DEA recommends disposing of unused prescriptions within 6-12 months of filling them. If you’re worried, check with your pharmacist about temporary storage options.

Will my doctor find out if I drop off my meds?

No. The DEA does not collect personal information at Take-Back Days. Law enforcement officers do not track who drops off what. Your privacy is protected by design. This is a public health initiative, not a surveillance program.

Write a comment

Your email address will be restricted to us